Collins, Lisa Gail

and Margo Natalie Crawford, eds. New

Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University

Press, 2006. Divided into three sections

---I. Cities and Sites, II. Genre and

Ideologies, III. Predecessors, Peers, and Legacies, this collection of essays

uses fresh research to deepen understanding of one of the most important

periods in African American literature, art, and culture. These inquiries

expose the lame tendentiousness of efforts, in certain sectors of literary

theory and criticism, to dismiss the value of the Black Arts Movement in our

nation’s literary history.

Davis, Thadious M.

Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, and Literature.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Discussions of “place”

have long been a staple of commentaries on Southern literature, but Davis

explores previously uncharted territories in her impressive, sustained twofold

argument: “First, African Americans who wish to have a regional identity as

southern can and increasingly are claiming that right. Second, the traditional

literature of the South has begun to acknowledge more fully the presence of

blacks and other minority groups within its ranks, including the previously

overlooked remaining southern Native American and Chinese populations or the

growing newer communities of Latinos, Vietnamese, and South Asians” (19). Davis’s intervention is timely, because it

casts light on the discrepancy between the evolving of literature and the

regressive social and political actions which do not bode well for a future in

the American South.

Elam, Michele. The Souls of Mixed Folk: Race, Politics, and

Aesthetics in the New Millennium.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press, 2011. Elam exposes the

deceptiveness of “post-racial” claims.

She “takes as a given the political nature, versus a presumed taxonomic

neutrality, of mixed race, beginning with the assumption that mixed race is no

fait accompli but still very much a category under construction”(6-7).

Fowler, Doreen. Drawing the Line: The Father Reimagined in

Faulkner, Wright, O’Connor, and Morrison. Charlottesville: University of

Virginia Press, 2013. This book is a good example of how lost in the critical wilderness

one becomes by following psychoanalytic maps of non-referentiality. Some critics find psychoanalytic theories to

be useful in reading texts, because those theories sanction language being in

conversation with language. One need not deal with the messiness of

referentiality that fiction and non-fiction invite. One can momentarily escape

the horror of knowing that signifiers co-exist with the material presences

which negate signification. What works for commentary on the magic realism of

Faulkner, O’Connor, and Morrison fails when it is applied to Wright’s scathing

realism. Fowler’s chapter “Crossing a Racial Border: Richard Wright’s Native Son” is disappointment. Fowler travels into the dense terrain of Native Son by following paths mapped by

Freud, Lacan and Kristeva, but she ignores the roadways Wright paved in The Long Dream and A Father’s Law. Failure to

discuss novels wherein Wright painstakingly “reimagined” fathers and sons is

poor scholarship.

Gotham, Kevin Fox.

Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture,

and Race in the Big Easy. New York:

New York University Press, 2007. Many books have tried to explain New Orleans

as a locus of virtue and vice. Lawrence N. Powell’s The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans (Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 2012), for example, focuses on risk and inventiveness as key

aspects of the city’s origins. But Gotham takes improvisation to a new level

with his surgical examination of how tourism creates and destroys the idea of

the city’s authenticity. Indeed, this study is quite the tool needed for

assessing the unique racism of New

Orleans and why the post-Katrina “new New Orleans” is an Eden for the rich and hell

for the displaced, the marginalized, and the working class.

Gwin, Minrose. Remembering Medgar Evers: Writing the Long

Civil Rights Movement. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013. Like her ground-cracking novel The Queen of Palmyra (New York:

HarperCollins, 2010), Gwin’s five essays provide extraordinary insights about

the discipline of history and about absorbing the significance of Medgar Wiley

Evers in the unfinished struggles of civil and human rights in the State of

Mississippi. Gwin’s sensibility as a creative writer who is also a scholar

enables her to make keen judgments about literary works by James Baldwin,

Margaret Walker, and Eudora Welty ; the aesthetic tensions among the Jackson Advocate, the Mississippi Free Press, the Clarion-Ledger and Jackson Daily News; the importance of Anne Moody’s Coming of Age in Mississippi (1968) and

Myrlie Evers-Williams’s For Us , the

Living (1967); the preservation and transformation of memory in music; the

commendable achievement of Frank X. Walker’s Turn Me Loose: The Unghosting of Medgar Evers (2013). Gwin’s essays

and bibliography are valuable resources for remembering or for learning why

struggles for humanity are always unfinished. This book should be read in

tandem with Michael Vincent Williams’s superb biography Medgar Evers: Mississippi Martyr (Fayetteville: University of

Arkansas Press, 2011).

Haile, James B.,

ed. Philosophical Meditations on Richard

Wright. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2012. These seven meditations comment

on Richard Wright’s incorporation of existentialist, ontological, and

phenomenological ideas in his fiction and non-fiction. They expose facets of Wright’s intellectual

imagination which are usually ignored or blurred in “traditional” literary

readings of his works.

Holloway, Jonathan

Scott. Jim Crow Wisdom: Memory &

Identity in Black America since 1940. Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 2013. Threaded with

astute references to the works of Richard Wright, Jim Crow Wisdom is a refreshing meditation on the uses of memory

and forgetting in the United States. Given the current trend of visualizing

enslavement and minstrelsy, Holloway’s comments on the filmmaker William

Greaves, a pioneering black documentarian, are invaluable. Holloway’s

conclusion is empowering: “…’home’ is a place where the possible and impossible

can commingle, where contradiction makes more sense than tidy narratives that

speak of unflinching progress, and where the psychological shelter of the

figurative can offer protection that is as real as the roof over one’s head”

(229).

Mullen, Harryette. The

Cracks Between What We Are and What We Are Supposed to Be: Essays and

Interviews. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2012. One of our most innovative poets and

scholars, Mullen possesses an independent spirit (do not confuse with “free

spirit”) which enables her to walk in balance with the arbitrary options of

languages and identities, to write poems and essays that do not bear the onus

of predictability. Her essays and

interviews tease us into profound reflection on ideas derived from her flexible

locations within African American, global and womanist traditions. Her burnished, critical independence

validates her choice “to explore diversity and variety rather than universality

or consistence” (262). It is reasonable to hazard that the essays “Evaluation

of an Unwritten Poem: Wislawa Szymborska in the Dialogue of Creative and Critical

Thinkers” (35-43) and “The Cracks Between What We Are and What We Are Supposed

to Be: Stretching the Dialogue of African American Poetry” (68-76) are exceptional

prose photographs of Mullen’s mind at work.

Norris, Keenan,

ed. Street Lit: Representing the Urban

Landscape. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2014. Norris’s penetrating article “The Dark Role

of Excess in the Literary Marketplace and the Genesis and Evolution of Urban

Literature” in JEAL: Journal of Ethnic

American Literature, Issue 1 (2011): 9-30 was a forecast for his editing of

this anthology of critical perspectives on Street Literature. He and the contributors rupture dated notions

regarding popular African American fiction and nonfiction, challenging us to

recognize the urbanity of the urban and to reexamine the bottomless well of

African American oral traditions. Thus, this anthology invites revised thinking

about narrow, purely academic canons of African American literature and why

large numbers of readers may find uncanonized works to be of great significance,

to be empowering equipment for the vexed navigations of everyday life. Omar

Tyree’s “Foreword” is itself a rewarding commentary on progressive creativity;

along with Norris’s pointed introduction, it provides a framework for dealing

with repressed dynamics in the evaluations of African American literature. Street

Lit extends the discourse on urban literature represented in Word Hustle: Critical Essay and Reflections

on the Works of Donald Goines (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2011),

edited by L. H. Stallings and Greg Thomas.

Osbey, Brenda Marie.

History and Other Poems. St. Louis,

MO: Time Being Books, 2012. Anointed with complexities, History and Other Poems is superbly executed. Brenda Marie Osbey’s poems invite exploration

of the chaos and créolité of history.

They urge us to attend to their nuances, to be renewed by radical, rich

aesthetic permutations. In her previous

collections ---- Ceremony for

Minneconjoux, In These Houses, All Saints: New and Selected Poems, and Desperate Circumstance, Dangerous Woman, Osbey acknowledged her

sustained research and investments in history. History and Other Poems

confirms her poetic mastery of time, space, and narrative, her authority to

guide us in the process of becoming enlightened by the profound structures of

existence. This is a rare book that

secures our participation in and control of the dialogic imagination.

Redmond, Eugene B.

Arkansippi Memwars: Poetry, Prose &

Chants 1962-2012. Chicago: Third

World Press, 2013. Redmond’s fame for his seminal work Drumvoices: The Mission of Afro-American Poetry (1976) and for his

photographs as cultural documents (see Howard Rambsy, “Eugene B. Redmond, The

Critical Cultural Witness.” JEAL, Issue

1 (2011): 69-89) often overshadows his achievements as a sound-driven poet,

founding editor of Drumvoices Revue,

and creator of the “kwansaba,” a demanding poetic form. Arkansippi

Memwars makes fifty years (1962-2012) of Redmond’s contributions to

literature and culture available for critical assessments.

Rowell, Charles Henry,

ed. Angles of Ascent: A Norton Anthology

of Contemporary African American Poetry.

New York: W. W. Norton, 2013. This anthology suggests that rap and hip

hop/spoken word creations have no place in contemporary poetry, and the Callaloo-canonized work included

presents a naïve view of dynamics in the field of poetry. Rowell’s belief that publication history

should trump autobiographical history is a major flaw, because it misinforms

readers about complexity and partisan contradictions. Equally flawed is his effort to assert that

poetry of the Black Arts period lacked “literary” importance, an effort that

merits non-academic condemnation. Rowell

would avoided glaring flaws of explanation had he read Eugene Redmond’s Drumvoices: The Mission of Afro-American

Poetry (1976), Kalamu ya Salaam’s What Is Life?: Reclaiming the Black Blues

Self (1994)and Lorenzo Thomas’s Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric

Modernism and Twentieth-Century American Poetry (2000) very carefully

before compiling and editing Angles of

Ascent.

Wilder, Craig Steven.

Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the

Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013). In

this exceptionally informative inquiry about the bloody origins of American higher

education, Wilder has constructed a brilliant model of what scholarship should

be. Just as Ira Katznelson’s Fear Itself:

The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright, 2013)

enhances the importance of Robert H. Brinkmeyer’s The Fourth Ghost: White Southern Writers and European Fascism, 1930-1950

(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), Wilder’s work lends an

urgency to serious engagement with Gene Andrew Jarrett’s Representing the Race: A New Political History of African American

Literature (New York: New York University Press, 2011) and John Ernest’s Chaotic Justice: Rethinking African American

Literary History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

Critical attention to the dazzling “funk” of variety and accomplishment in

contemporary African American literature should be balanced by scholarly

attention to texts which are generic foundations for the forms and content of

black writing from 2000 to the present. To increase the possibility of having a

larger selection of informed African American literary histories, it is

essential that younger scholars be encouraged by the majesty of Ebony and Ivy to do archival work and to discover the

problematic and enlightening pleasures of documents which are crucial for understanding

the conditions of the twenty-first century .

Jerry W. Ward, Jr.

December 7, 2013

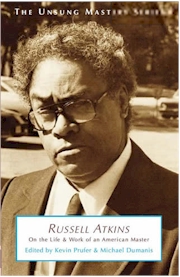

Russell Atkins: On the Life & Work of an American Master

Russell Atkins: On the Life & Work of an American Master