CHINA IV is coming.

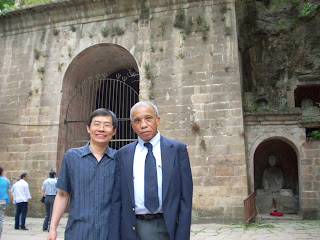

Yukuo and I

have great respect

for things ancient and spiritual.

Saturday, July 21, 2012

Reading Notes

Morrison, Toni. Home.

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

The

Nobel Prize in Literature is the most prestigious award the West offers to

writers, but one might ponder whether it is a curse or a blessing for those who

earn it. Does a writer’s creative powers

decline or hibernate after she or he receives the award?

Judgment

is so privatized and relative in the twenty-first century that it matters very

little if a reader says “Yes” or “No.”

Value is a pragmatic commodity.

It has the stability of a theorized subatomic particle. Only a statistically insignificant portion of

the world’s population gives more than a few seconds of thought to the growth

or stasis or decline of the writer’s imagination. No writer can maintain stellar performances

over several decades of doing things with words. But prizes create unreasonable

expectations. Writers who possess them

are often more harshly judged than their peers who create excellent works in

oblivion.

Such is

the case with Toni Morrison since she won the ultimate literary prize in 1993. Not even the protective circle of the Toni

Morrison Society can deflect barbs of disappointment, the neutrality one feels

after reading Home (2012). When you compare it with earlier novels ---The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon, Beloved,

or Jazz, you think the early works

have the signature richness and depth of songs by Etta James, Billie Holiday,

Nina Simone, and Sarah Vaughn. Paradise,

Love, A Mercy, and Home are good but

not overwhelmingly exciting. They are like the singer who scored number one on

last week’s pop chart. You are disappointed that these later works do not light

your fire.

Bernard

Bell aptly claimed in The Afro-American

Novel and Its Tradition that Morrison’s fiction was marked by poetic

realism. In Home, realism has been displaced by cruel ironies of postmodern poetry. Its plot is recognizable but thin. Morrison

indulges her privileges. The narrator’s language

floats above the story’s engagement with obscene racism, because Morrison

contemplates her cleverness in the use of language more than she uses language

to provoke consciousness of America’s social and cultural filth –systemic

brutalization of black sensibility, medical experimentation on black bodies

worthy of a Nazi doctor. Its examination

of manhood in post-Korean War

America focuses on the fragility of male subjectivity, while its portrayal of boyhood displays remarkable strengths. Superb imbalance. The protagonist Frank Money nurtures too much

grief and self-pity. “In Frank Money’s

empty space real money glittered” (84). He is truly not “some enthusiastic

hero” (84). When the language of the novel

is not laughing at the reader, it is sweating the reader. It invites hostility and displeasure.

We

should have respect for Morrison’s achievements. Scholars are obligated by literary history to

read her writings –all of them. But

scholars like casual readers do not have to like all of her work, and they are

free not to tarry in the new “home” she has constructed.

J. W. Ward, Jr. ---July

20, 2012 Reading Notes

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)